Last year, when I was teaching Sunday school through Book 3 of the Psalms (Ps. 73-89)—a section of the Psalter largely composed in response to conquest and exile and steeped in lament and imprecatory language—I inadvertently taught a really difficult first-Sunday-of-Advent lesson because Psalm 79 was the next Psalm up in our series.

"How long, Lord? Will you be angry forever? How long will your jealousy burn like fire?" (v. 5).

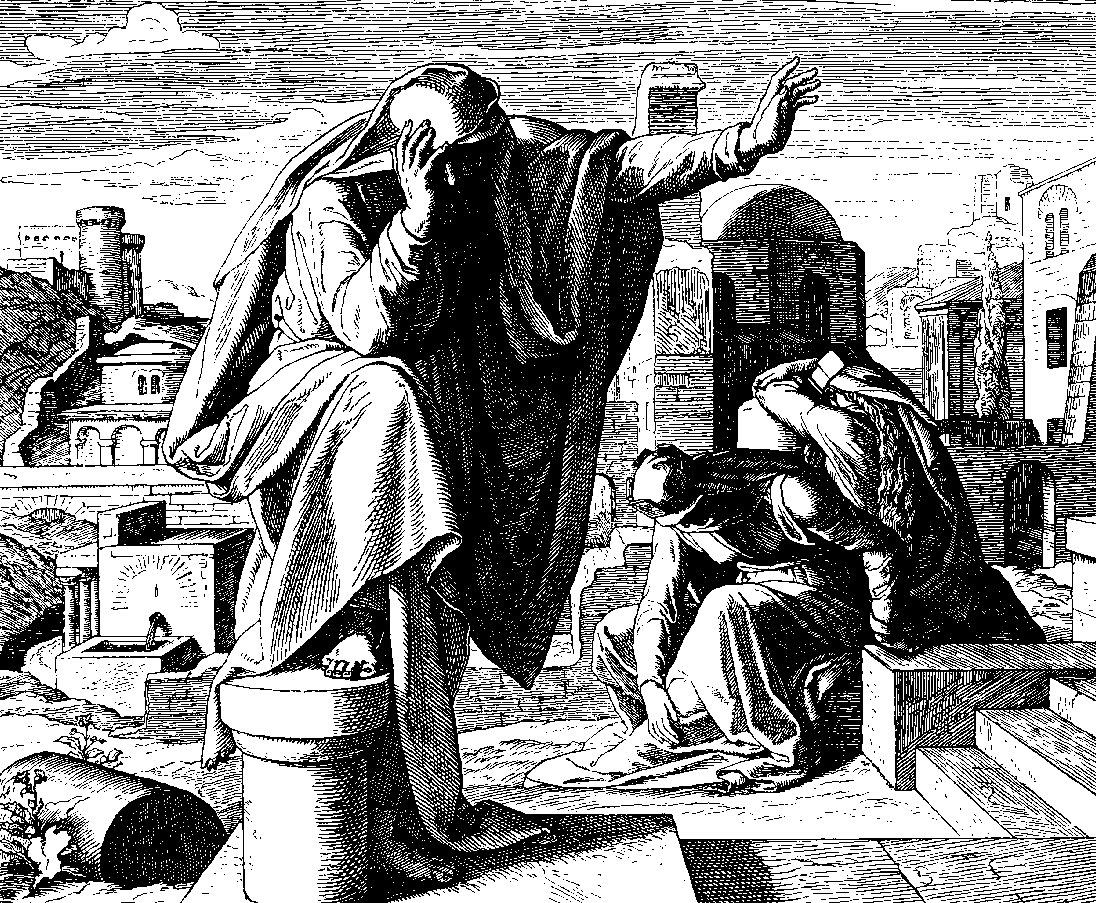

This is a Psalm reflecting on the exile, but rooted in the grotesque imagery of dead bodies left unburied for consumption by wild animals (vv. 2-3), a common motif of divine judgment texts and an explicit fulfillment of the promised curse of Deut. 28:26. The Psalmist, in effect, is leading the people in corporate lament that God keeps His promises to judge their wickedness when they have been unfaithful (vv. 1-7), while then leading them in prayer that God will keep His promises to save His people and judge those who reject His name (vv. 8-13).

The catch is that in verse 2, we find out that it is God's servants and "your faithful ones" (חֲ֝סִידֶ֗יךָ, literally "your doers of chesed" or covenant faithfulness) who suffer as well. The righteous judgment of God for the wickedness of the people as a whole also falls on the righteous remnant.

The New Testament tells us that judgment begins with the household of God (1 Pet. 4:17), and these faithful ones long for God to rise up and fulfill all His promises, but they never plead their own righteousness. Rather, they pray for God to save them and crush their enemies to vindicate *His* righteousness. “Help us, God our Savior, for the glory of your name; deliver us and forgive our sins for your name’s sake!” (v. 9). They trust that God will send His deliverance, his Messiah, as He has promised, and they pledge that they will continue to praise Him, generation to generation in light of that (v. 13).

From our New Testament vantage, though, we see that when the Messiah did come, He did not destroy the enemies of God's people. Rather, He stood in judgment over the scribes, Pharisees, and teachers of the law—those who claimed to lead the household of God who instead burdened the people and led them astray.

When the Messiah did come, He did not immediately save His people from earthly oppression. Rather, He was publicly displayed as a curse accepting the promised judgment—even though He perfectly served God and was perfectly faithful (Isa. 53). And in light of that, we—the church, the generations to come—praise God for His atonement and deliverance from the curse of sin.

The Lord has come.

Even still, we cry with the Psalmist, "How long, Lord?"

Even still, we wait for the end of the story and cry with the martyred saints under the altar "How long, Sovereign Lord, holy and true" (Rev. 6:9-11)?

The Lord will come again.

Advent calls us to hold God's apparent inaction in the present in tension with His ever-faithful deeds and unfailing promises in the past.

The Lord has come and will come again.

Come, Lord Jesus.